Why Venture Capitalist and Tech Founder Jewel Burke Always Has Two Jobs

Systemic racism has created a world where I and many other Black people literally have to work twice as hard to get half as much.

Since I’ve been able to work, I’ve worked multiple jobs. During summers growing up, I worked in the businesses started by my grandparents in Mobile, AL, and passed down to my father and his siblings. You could find me doing everything from working the register at their BP gas station to preparing sandwiches in my father’s Subway. When I went to college, despite having a full-ride academic scholarship at Howard University, I took full advantage of work-study opportunities — working “security” in the evenings at the School of Business and working in the afternoons as a part-time instructor at MS², Howard’s on-campus Middle School for Math and Science. Even as I worked my first full-time job at Google, I moonlighted as a fashion model, signed to the now-defunct, San Francisco based, City Model Management, and doing runway shows and local advertisements on the evenings and weekends to bring in an extra thousand dollars per month. Fear of being stuck in a generational cycle of debt and financial insecurity or not having enough money to pursue my dreams has always been a driving force in my life and decisions.

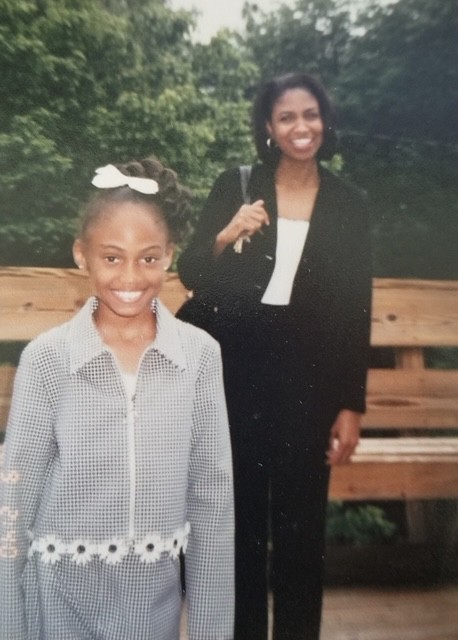

When I was a little girl, I saw my mother work long hours to start her own business

When I was a little girl, I saw my mother work long hours to start her own business — an insurance agency that she’s now run for nearly 25 years. In the early days of her business, I saw her cry when she didn’t have enough money to pay herself, or when she couldn’t afford to enroll me in dance lessons because money was low. I saw her wrestle with the racism and prejudice she faced from customers and as new books of business were doled out — where she seemingly always got the scraps. In my teenage years, her business became more stable and prosperous as she grew her base of loyal customers and became a leader in the community. However, at that same time, I witnessed my father’s family businesses get squeezed out by large oil companies that had instituted discriminatory pricing, which did not leave room for a profit at the handful of gas stations our family-owned. I saw the heartbreak my father endured as he lacked the resources he needed to fight to keep them alive.

I learned that racism would play a role in my journey

My biggest takeaway from watching the entrepreneurial journeys of both my parents was that in order to achieve any level of success I would have to work harder and sacrifice more than most. I learned that there would be many things I cannot control in life and business — but the one thing I can always control is what I put into achieving any goal. I learned that racism would play a role in my journey, but I must never let it knock me off my path. I also realized that because of the turbulence of their entrepreneurial paths, my parents were not in a position to help me financially as I transitioned into adulthood. I decided that I should put myself in a position to help them, my family and community, instead.

When I came up with the idea for my startup Partpic in December 2012, I’d already started saving money to go back to school to get my MBA. I knew I wanted to minimize the amount of debt I needed to take on to do so. I distinctly remember being inspired by Elliott Robinson who spoke to my Management Leadership for Tomorrow (MLT) MBA Prep cohort and described how he worked full time as a VC at Syncom while getting his MBA at Columbia. I spoke with my coach about the feasibility of doing something similar because I couldn’t fathom going two years without a salary while also taking on debt. As my coaching calls continued, the conversations shifted from planning my responses to essay questions, to me telling my coach the details of Partpic. With her blessing and nudge that I could always pursue business school at a later time if things didn’t work out with my idea, I decided to re-purpose the money I’d saved for business school to launch Partpic.

As I started Partpic and began to use the money I’d saved to cover my bills and to pay early contractors who I’d brought on to build the first prototypes of Partpic, I quickly realized that the distance between where I was with the technology and where I’d need to be in order to begin generating enough revenue to sustain was more than I’d saved up. So I reverted back to what I’ve always known I can do — work more. I collaborated with my mentor, Chris Genteel, on a plan for me to return to Google in the capacity of Entrepreneur in Residence. Chris led Google’s business inclusion efforts and saw an opportunity for me to rejoin with the specific goal of teaching other underrepresented small business owners how to use Google products in their businesses by hosting workshops and speaking at various conferences around the country. This role gave me the ability to earn a paycheck and continue working on Partpic. The money I earned went to pay contractors for early development work. It also allowed me to buy my first home, which I later used as collateral when I took out a loan to float Partpic when the negotiations with Amazon took longer than expected and as we were boxed out of raising additional financing. Lastly, my stock units that had vested over the nearly 3 years I worked at Google while building Partpic, gave me a last resort option when I needed one more month of runway to pay my team of 14 people. I was able to cash in my stock and pay my team to ensure we never missed a payday. The money I raised for Partpic ($2.1M) was not enough to get the business to the finish line and most investors did not have enough conviction in me/the business to reinvest when they had the opportunity. I had enough conviction to cover that gap and had faith that my hard work would pay off. It did, and we signed the deal to sell Partpic to Amazon on October 31, 2016. Betting on myself has yielded me an incredible return on my investment in the business. We will never know how much more some investors could have yielded had their decisions not been clouded by bias.

Generational wealth for my family — not a personal victory

Although I was able to make a life-changing amount of money through the sale of Partpic, I’ve always viewed this as a foundation of generational wealth for my family — not as a personal victory. Where my parents were not able to assist me financially, I have positioned myself so that my younger siblings and future children will not have to struggle financially. While at Amazon, I began to think deeply about what I wanted to do next. I had a persistent desire to right a wrong I saw in my own journey. I knew that many investors had not given me a fair shot because of my identity as a Black woman building in the south and I wanted to ensure that other Black entrepreneurs didn’t experience the same obstacles. I began angel investing in 2017 in companies with checks ranging from $10–60K and I realized that given the high-risk nature of startups and the long return cycles, I’d run out of personal capital to invest and would need to find ways to scale my approach. As I was approaching three years at Amazon (the required number of years for me to vest the deal stock from the sale of Partpic), though incredibly tempted to take a break and reflect on what had happened in the 7 years prior, I decided that I would need to continue to work to fulfill the purpose that had been nagging at me. I joined forces with my friends and fellow entrepreneurs Justin Dawkins and Barry Givens and threw my attention to the establishment of our fund, Collab Capital — to invest in more Black entrepreneurs and do it in a way that better aligns the interests of those entrepreneurs to us as investors.

As I learned more about the development of a fund, I realized it would require a substantial financial investment (in the neighborhood of $1.5M from the GP) to establish it. For one, most institutional investors require a track record of investments. I’d invested about $300,000 of personal capital into startups to support founders I believed in and to learn more about investing. However, in early Limited Partner (LP) discussions, I realized that for some this did not meet their threshold for track record given the dollar amounts invested and relative newness of the companies. Given Collab Capital’s unique profit-share model, legal costs for new documents meant substantial upfront investment. Additionally, the traditional fund structure of a 2 and 20 model means that as fund managers we can draw 2% management fees when the fund is raised to run the fund and bank on receiving the majority of our compensation as carrying in the fund after we’ve returned initial investments to our LPs. However, in order to establish and raise the fund — which can take up to two years on average — we’d have to self fund the operation.

As I was thinking through these realities, I learned of a new role at Google to lead Google for Startups in the US. I decided to interview for the role because I knew that in every way possible my 30s would be dedicated to righting the wrongs I experienced as a startup founder in my 20s. I saw the opportunity to lead at Google as a chance to increase my capacity to level the playing field for underrepresented startup founders and help steer Google’s work in this area. Because I’d done it before while building Partpic, I knew that I could take on the responsibility of a role at Google while also leading the establishment of and fundraising at Collab Capital. I also knew that taking on the job would help alleviate some of the financial burden of establishing Collab Capital completely out of the nest egg I established via Partpic. Lastly, I knew that in the same ways people doubted my ability to lead Partpic and work at Google, that they would also question my decision to lead Collab Capital and work as Head of Google for Startups, US.

As our country faces the most captivating racial reckoning of our lifetime, I am challenging everyone to think differently about the rules and systems they covet and who those rules and systems are keeping from opportunity. I offer the following questions for consideration to LPs who have disqualified Collab Capital because I hold multiple positions as we establish the fund and anyone else who looks down on emerging fund managers who find creative ways to break into the industry:

- Without family support and/or generational wealth, how would one be able to bear the costs of establishing a new fund?

- Is holding multiple positions only acceptable for rich, powerful white men like Jack Dorsey, Elon Musk, or Jeff Bezos, each of whom owns/runs multiple large corporations simultaneously?

- What does meritocracy mean to you? Can its promise be achieved if only wealthy people have an opportunity to succeed?

Thank you for considering these thoughts and questions. I welcome dialogue about what we can do as a collective to ensure future generations of Black people and people from other historically disadvantaged groups do not have to work twice as hard to simply have a chance at building generational wealth and participating fully in the innovation economy.