Black Engineers You Probably Weren’t Taught About Who Did Amazing Things

Throughout history, engineering was almost entirely the domain of white men, for example, it was in 1892 that The Massachusetts Institute of Technology had its first African-American graduate, Robert R. Taylor.

It was only 25 years later, in 1917, that the university gave its first civil engineering diploma to an African-American.

Although we’re in 2022 – the pictures are still relatively similar – white men still dominate the industry.

The UK has one of the most male-dominated engineering sectors, Male academic scientists outnumber their female counterparts by two to one in biology, mathematics, and physical sciences in the United Kingdom, and by more than four to one in engineering and technology, according to an official report collated for the government and released last month.

In the US – the numbers are similar. Engineering is the most male-dominated field in STEM. It may perhaps be the most male-dominated profession in the U.S., with women making up only 13% of the engineering workforce.

But when we break down these figures you’ll find very few of these women or men are from the Black, Asian or Latinx community.

Here’s we’ve highlighted 3 amazing engineers who you should know.

Walt Braithwaite

Born in Jamaica, Braithwaite received a degree in engineering in 1966 and joined up with Boeing the same year. Just as commercial flying was taking off, Braithwaite began flying up the ladder, leading and developing some of the most important aircraft and systems, according to a 1996 Seattle Times report.

Back then he was described as a “formidable, sometimes contradictory mix of talents: A private, quiet man who has been a strong team player at Boeing for 30 years.”

The hands-on machinist, who created engine systems in the abstract, was one of the early pioneers of what we now know as CAD – Computer-aided design.

Braithwaite’s team developed computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) systems for Boeing, which led the way for airplanes and, eventually, many other products designed entirely through software.

Ursula Burns

Burns is the first African-American woman to lead an S&P 500 company. In 2015, she helped generate $18 billion in revenue, with adjusted earnings per share of 98 cents, all down slightly from a year earlier.

After six years as Xerox CEO, she stepped down after the company split into two public companies: Conduent, a $7 billion business process outsourcing company within a tax-free structure, and the new Xerox, an $11 billion standalone company focused on document technology for which Burns was named chairwoman.

Burns joined Xerox fresh out of Columbia University, where she received her master’s degree in mechanical engineering

She turned around a fading company mainly known for paper-copying machines into a profitable business services provider. She left Xerox in 2017 and currently serves on various boards.

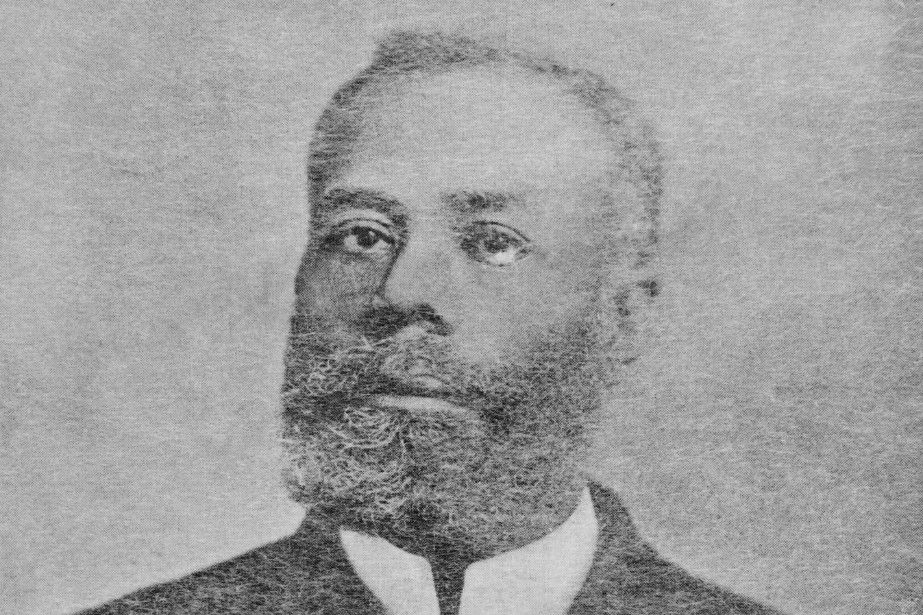

Elijah McCoy

McCoy was born on this day in 1843 to George and Emilia McCoy, former slaves from Kentucky who had escaped to Canada on the Underground Railroad. After living in Ontario for several years, the family moved to Detroit following the Civil War.

He even traveled to Scotland at the age of 15 for an apprenticeship and came back with a mechanical engineering degree.

Although McCoy was educated as an engineer, writes the Canadian Railway Hall of Fame, the discriminatory management of the railroad thought a black man couldn’t be an engineer, and he was hired to work in the boiler room of trains as a fireman.

It wasn’t until McCoy received his first patent in 1872 for an automatic oiling device for the moving parts of steam locomotives, colloquially known as the “oil-drip cup” that things started to change.

“McCoy’s patented device was quickly adopted by the railroads, by those who maintained steamship engines and many others who used large machinery,” writes the University of Michigan.

“The device was not particularly complicated so it was easy for competitors to produce similar devices. However, McCoy’s device was an original development and, apparently, had the best reputation.” That may well have been how the phrase “the real McCoy” became popular, the university writes.

McCoy used some of the money from ventures associated with his first patent to continue inventing, coming up with mostly railway-related inventions but also an improved ironing board.