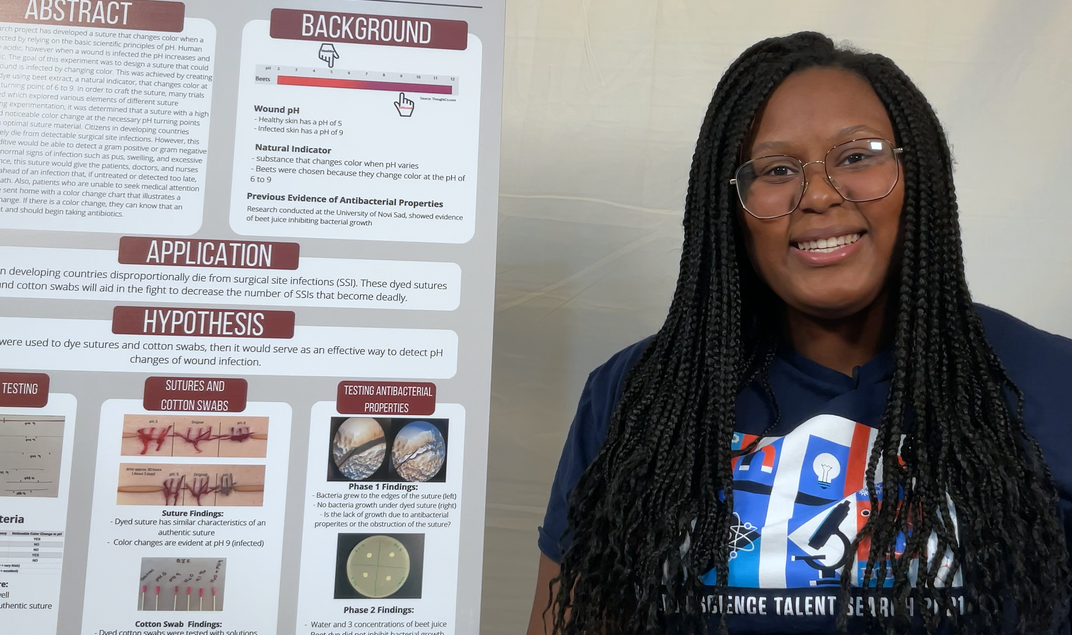

Meet Dasia Taylor, The High Schooler That Invented Color-Changing Sutures To Detect Infection

A 17-year-old student at Iowa City West High School has invented color-changing sutures to detect infection and is now set on getting it patented.

Working with an eye on equity in global health, Daisy Taylor hopes that the color-changing sutures will someday help patients detect surgical site infections as early as possible so that they can seek medical care when it has the most impact.

Daisy began working on the project back in October 2019, after her chemistry teacher shared information about state-wide science fairs including the Science Talent Search competition.

Eager to take part – the teen started doing some research.

Infections after Cesarean sections reportedly caught her attention and inspired her research. Through her reading, she found that up to 20 percent of women who give birth by C-section in some African nations then develop surgical site infections.

Research also shows that health centers in Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Burundi have similar or lower infection rates, at between 2 and 10 percent, following C-sections than the US, where rates range from 8 to 10 percent.

Taylor had read about sutures coated with a conductive material that can sense the status of a wound by changes in electrical resistance and relay that information to the smartphones or computers of patients and doctors. according to Smithsonian mag.

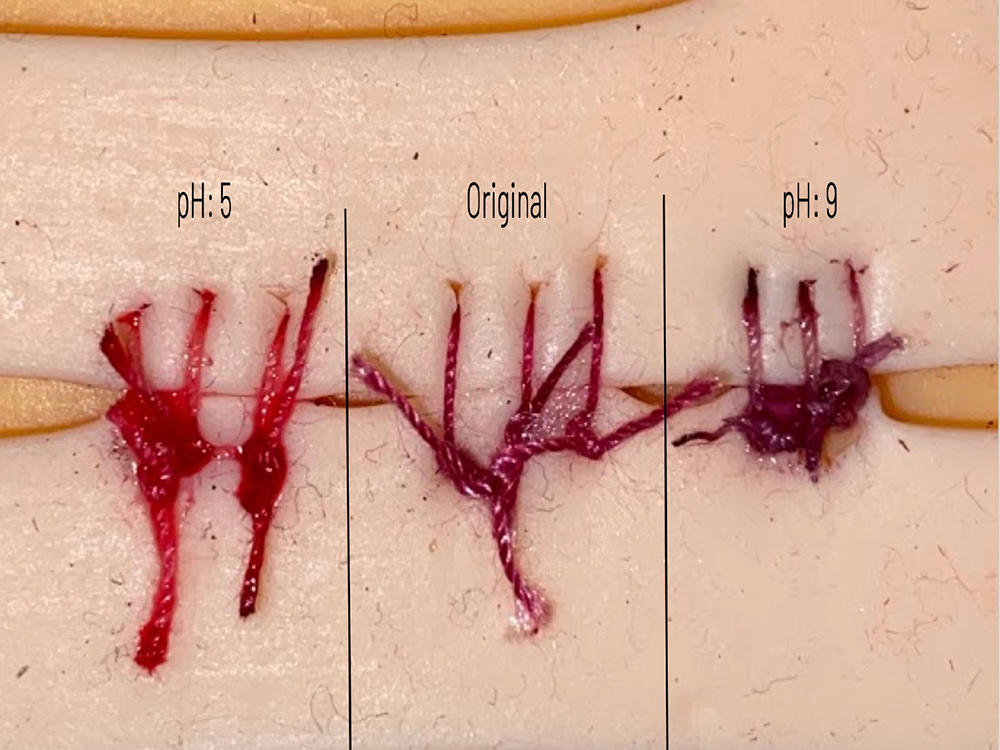

The magazine reports that healthy human skin is naturally acidic, with a pH of around five. But when a wound becomes infected, its pH goes up to about nine. Changes in pH can be detected without electronics; many fruits and vegetables are natural indicators that change color at different pH levels.

“I found that beets changed color at the perfect pH point,” says Taylor. Bright red beet juice turns dark purple at a pH of nine. “That’s perfect for an infected wound. And so, I was like, ‘Oh, okay. So beets is where it’s at.”

Taylor then had to find a suture thread that would hold onto the dye.

She tested ten different materials, including standard suture thread, for how well they picked up and held the dye, whether the dye changed color when its pH changed, reported Smithsonianmag, before looking into how their thickness compared to standard suture thread.

After her school transitioned to remote learning, she could spend four or five hours in the lab on an asynchronous lesson day, running experiments.

A cotton-polyester blend checked all the boxes. But, after five minutes under an infection-like pH, the cotton-polyester thread changes from bright red to dark purple. Then, after three days, the purple fades to light gray.

Taylor plans to patent her invention. In the meantime, she’s waiting for her final college admissions results.

But studying bacteria requires specific, sterile practices that neither Taylor nor her mentors Walling and Michelle Wikner, both chemistry teachers, were initially familiar with.

In the months leading up to the Science Talent Search competition, Taylor connected with microbiologist Theresa Ho at the University of Iowa to create a research plan incorporating the proper techniques, and that work is ongoing.

Maya Ajmera, the president and CEO of the Society for Science, which runs the Science Talent Search, told the magazine: “To get to the Top 40, this is like post-doctoral work that these kids are doing.

“This year’s top prizes went to a matching algorithm that can find pairs in an infinite pool of options, a computer model that can help identify useful compounds for pharmaceutical research and a sustainable drinking water filtration system. The finalists also voted to grant Taylor the Seaborg Award, making her a spokesperson for their cohort.