The Myth of ‘The Visionary Founder’

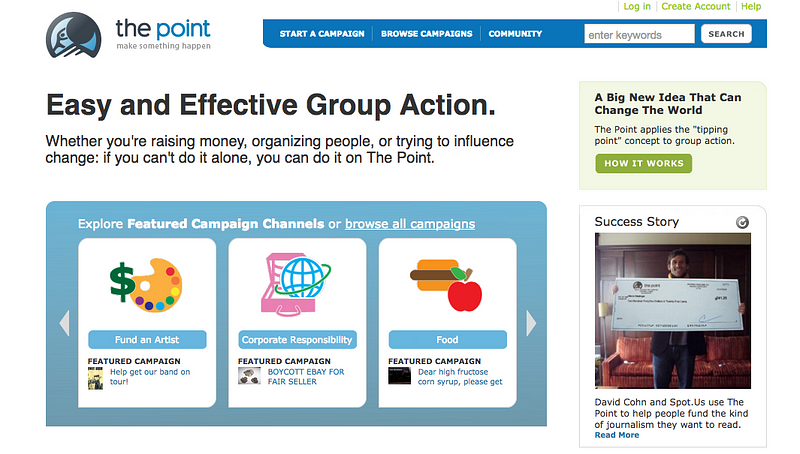

During an entrepreneurship talk, in Prof Darragh’s class while at Booth School of Business, I listened to Andrew Mason talk about ‘The Point.’ This was 2009 and Andrew talked about signing people up to collectively fight for or contribute to causes and initiatives that they cared about. Sort of a mass protest platform for the digital age. Andrew had amassed a list of do-gooders and would unleash it on all the necessary causes. It was similar to Change.org and had been started around the same time. Even if it was a copycat of Change.org, there was nothing wrong with that.

Fast forward a year and that list of web dwelling protesters started getting corny and funny emails selling them coupons. Fast forward a year, The Point had become Groupon and that seemingly unsure founder, Andrew, was confidently waxing lyrical about the impact Groupon could have on small businesses worldwide.

According to Nick Bilton’s ’Hatching Twitter,’ and a story we all now know so well, Twitter came out of the remnants of a podcasting platform called Odeo. Odeo was founded by Noah Glass and funded by Ev Williams and other investors. Most of these other investors were ready to give up on Odeo when Apple came out with iTunes in 2005, but Ev Williams suggested that the team of ~12 people they’d put together come up with new ideas. One of those team members was Jack Dorsey, and he came up with the notion for short messaging platform. Twitter was born. It wasn’t born from some grand vision about how they could change the world and fuel revolutions, which the platform would eventually do, it was more about survival…

I talk to a lot of founders, and there is this narrative that’s seeped into the startup founding story; the belief now is that you need an enormous world-changing vision before you can start your business. That, without a business idea that is unique and wholly original, you should not be working on a startup. The myth is couched in questions like ‘what is your competitive advantage and where will you be in 5 years?’. These questions have led many founders to question the value of their, often, simple sustaining innovation. These questions put up unnecessary mental barriers to entrepreneurship for the vast majority of people out there. This shouldn’t be because, in the early days, there is very little certainty about where a startup is going… Even in the introduction for Founders at Work, Jessica Livingston talks about the feelings of uncertainty the famous founders she interviewed for the book felt about their ideas. Writing about founders of popular companies like Craigslist, Firefox, Apple, Adobe, 37Signals, etc., she shares

Phil Knight didn’t know what he was doing or going to do with his life. He was in the financial services industry but knew he was obsessed with feet. Especially running/runner’s feet. In ‘Shoe Dog,’ Phil Knight decided to travel the world with his buddy and ended up finding his calling. From the book, we learn that Phil Knight did not even sell his shoes for the first few years of running the Blue Ribbon Company. That company would later become Nike. Knight would go on to create his shoes. But only after some shenanigans by managers at Onitsuka, the brand of shoes Blue Ribbon carried in the US. For the first 10 or so years of Nike, the company was tethering on edge. Phil Knight was always hopeful but, according to the book, this was less about a grand vision during the daily grind and more about just his force of will and cunning to keep the company alive.

The Warby Parker story, as told in ‘Originals,’ highlights another element to the founding story. A story that if you listen to investors and another folk who have bought into start-up myths, denigrates the founders who choose to take a more realistic view of founding a business; the myth that founders who stay in their day jobs until their business gets some traction are ‘less committed. I can attest to the fallacy of this myth; I moved to this country from the UK, got married, started business school and founded Power2Switch. Believing the myths about founder commitment being about not doing anything else, I plowed head-on into working on the business for no salary for the first two and half years. It left me in debt (emotionally and financially). I’m still recovering from that mistake. I wish I had acknowledged that my context should have provided my metric for what a founder looks like. But now I know.

In Originals, it’s shared that three (3) of the Warby Parker founders, who were students at Wharton business school at the time of the company’s founding, took internships even as they modeled the company in spreadsheets and continued their research. They didn’t drop it all to pursue some world-changing vision that consumed them. No, they were measured in their approach even though ‘The Social Network’ had popularized the myth that you had to drop out of college to show the commitment required to build a tech venture truly. Only one of the founders worked on Warby Parker between the founder’s first and second years of business school. At this point it was not about changing the world, it was about figuring out a sustainable business model.

While we shouldn’t focus on the grand vision (or lack of) in the daily existential crises of the early days of a startup, what we should concentrate on is what the founders in all the stories above did; they went ahead and put their hands to the grind towards building their businesses. Time and time again, what is clear is that one does not get anywhere without doing the very next thing in front of you as a founder. The grand ‘I-want-to-change-the-world’ vision comes as progress is made day by day and the existential crises recede from being daily, to weekly and then monthly. Assessing the results of the work done and the lessons learned from the day to day is how most of these founders got to their grand world-changing visions, which led to their billion-dollar businesses.

And so that’s what I tell the early stage founders I chat with; I just tell them to do the next thing and forget about the grand vision, for now, your job is to stay alive long enough to develop a grand vision. Truth be told, some of these grand visions from successful founders are developed in hindsight, anyway.