Brothers Created Alphabet To Save Their Language From Extinction, Now Integrated Across Microsoft Platforms

Over thirty years ago, Guinean brothers Ibrahima and Abdoulaye Barry created ADLaM, new alphabet for the Pulaar language of the Fulani people of West Africa.

Now, Microsoft 365 has integrated the redesigned alphabet into its global platforms, helping to preserve the language for years to come.

Disappearing languages

Every three months, a language becomes extinct. happens every three months. As much as 90% of the world’s 6,500 languages are expected to disappear by the end of the century.

Although over 40 million people speak it, for most of its history, Pulaar never had an alphabet. To send a message, Fulani people had to translate messages into and back out of a script that was not their own. As the need to communicate via text increases, languages like Pulaar are put at risk.

“In parts of Africa, anyone who doesn’t know how to read or write in French is considered illiterate,” says Abdoulaye Barry, who now lives in Portland, Oregan.

“It is not uncommon for regimes, especially those with a colonial heritage, to be suspicious of efforts to popularize ‘unofficial’ writing systems. Policing the written word is a way to exert control.”

Preserving Pulaar

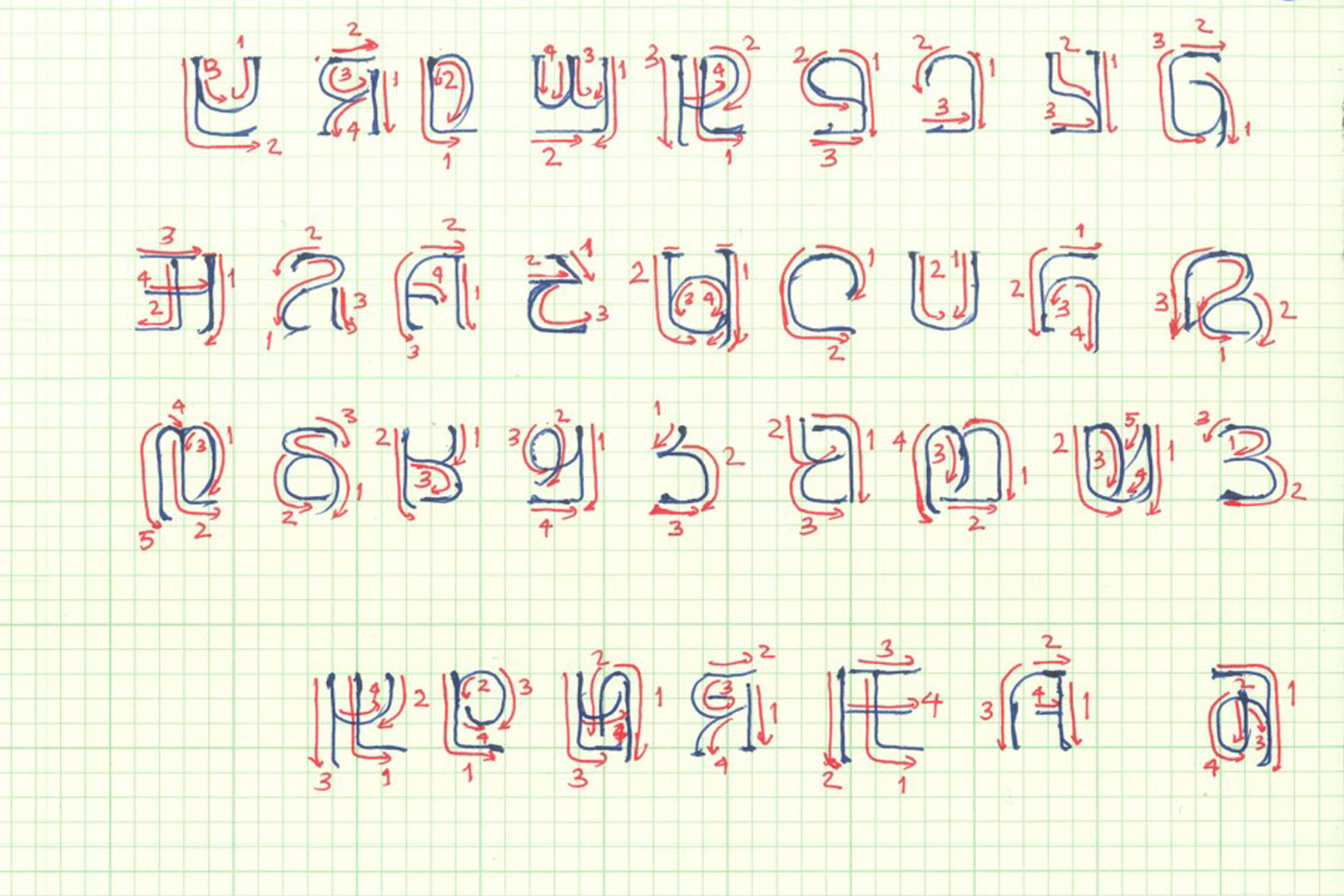

Determined to preserve their native language, in 1989, when Ibrahima was 14 and Abdoulaye was only 10, the brothers began working on their alphabet. Within six months, they’d developed a working script: 28 letters, written right to left, like Arabic.

The boys shared their alphabet with anyone who showed interest and over the alphabet spread in the years that followed.

It went on to be known as ADLaM, an acronym using the alphabet’s first four letters, which stands for Alkule Dandayɗe Leñol Mulugol, or “the alphabet that protects the people from vanishing.”

The brothers later developed early versions of the digital typeface before partnering with McCann New York and a group of expert typeface designers to create a revised version of the alphabet that was easier to read and write.

Taking ADLaM online and beyond

ADLaM has been successfully embraced by the Fulani, and the alphabet has gained popularity in the community across West Africa and the Fulani diaspora worldwide.

McCann and the brothers have also created educational materials for Guinean schools, including a children’s book designed to teach the ADLaM alphabet and elements of the Fulani culture, in-classroom learning materials, and a learn-to-write book.

The alphabet has also been recognized as an official alphabet by the government of Mali, clearing the way for children to learn ADLaM in government-run schools. The first two ADLaM-focused schools will open this year in Guinea and will allow Fulani children to study a full curriculum in their own language.

“ADLaM has increased the chance of the language to survive, even in areas where the language has been dominated. We have our own alphabet! That’s a source of pride,” said Abdoulaye Barry.

Microsoft has now integrated the redesigned alphabet across its global platforms. A new typeface, ADLaM Display, has been made available as a free download to use on Microsoft 365 apps and elsewhere, connecting Fulani people across the globe.